10/02/2007

FEATURE BY MIKE LAWRENCE

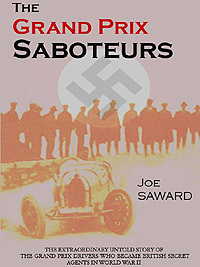

Joe Saward's Grand Prix Saboteurs has been a long time in arriving, eighteen years, and it is worth every minute of the wait.

Joe Saward's Grand Prix Saboteurs has been a long time in arriving, eighteen years, and it is worth every minute of the wait.

It tells the story of three racing drivers who were involved with the French Resistance during WWII. There was William Grover Williams (right), who raced as 'Williams' and who was the most successful British driver of the 1920s. He won the first Monaco GP, the French GP twice and the Belgian GP. His father was English, his mother French. He grew up in France and perhaps became more English because of that.

Williams was recruited by the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and parachuted into France in 1942 to organise cells which would cause mayhem in support of the inevitable Allied invasion. It was no easy task, France was the only country to sign an armistice with Germany and, having lost 1.7 million dead in WWI, with countless more maimed, the French were not actually straining to become involved.

Joe Saward quotes a former SOE agent. "To understand the French Resistance you must think of an egg timer which was turned on its head when the Germans invaded France in 1940. The first grain of sand was called Charles de Gaulle and gradually others joined him. By the end of the war everyone in France was a member of the Resistance."

'Everyone' includes the collaborators, those who betrayed their Jewish neighbours and those who were able to wriggle out of the fact that they had joined the Waffen SS. Joe and I discussed this latter category more than 16 years ago and we had in mind a person known to us both.

Grover Williams (he had hyphenated his name by then) recruited his old friend and rival, Robert Benôist (left) who, in 1927, won four of the five Grands Prix. He had been World Champion in all but name. There had been a World Championship, but only for manufacturers. That had been won by Delage, with Robert taking all of Delage's wins. He became Competition Manager for Bugatti and came out of retirement to win Le Mans in 1937.

Grover Williams (he had hyphenated his name by then) recruited his old friend and rival, Robert Benôist (left) who, in 1927, won four of the five Grands Prix. He had been World Champion in all but name. There had been a World Championship, but only for manufacturers. That had been won by Delage, with Robert taking all of Delage's wins. He became Competition Manager for Bugatti and came out of retirement to win Le Mans in 1937.

Benôist was anxious to recruit Jean Pierre Wimille, another outstanding driver. Grover Williams was wary of Wimille, who had flirted with right wing politics, and refused. When, in 1943, the Englishman was betrayed by someone he had every reason to suppose was a friend, Benôist assumed leadership of the cell and brought in Wimille. He had no reason to regret his decision.

In the late 1930s, Jean Pierre Wimille was recognised as being among the very best drivers in the world, so much so that Mercedes Benz offered him a drive. J P turned down the offer on the grounds of patriotism, he knew that war was inevitable, and so became possibly the only driver to turn down either of the 'Silver Arrows' teams . In the immediate postwar period, Wimille was widely felt to be the world's top driver, he was with Alfa Romeo, but was killed while practising for a race in Argentina in 1949.

We have secret agents who were all Grand Prix winners, operating in wartime Paris. It's a gift of a story.

Joe and I had a long conversation about his project in 1990 and I was very impressed at the research he had done then. It was outstanding by any standards, it was PhD level. He had interviewed fellow agents, surviving relatives and sifted through files, then everything went quiet.

|

In the meantime, Robert Ryan wrote a serviceable novel, Early One Morning, based on the story. It was a pleasant read at the time, but unmemorable. Someone else published a theory which claimed that Grover Williams survived the War and worked for British intelligence under a different name. The story was in the ether and I feared that someone would pre empt Joe's account.

Joe's Foreword said that he needed convincing to complete the work. As a researcher myself, I think that he knew in his bones that his research was not complete, and would only become complete when secret files were made public under the 50 year rule. I know that he had hoped to get some details from German documents which had been transported to Moscow in 1945.

Joe had most of the story a long time ago, it was his integrity as a researcher which prevented him from rushing into print. What then happened was that the story brewed in his mind for years so he became familiar with every aspect.

A common fault among writers of history is that they feel compelled to add unnecessary detail to prove that they have researched it. They cannot simply say that a candle was lit, they have to tell you something about the candle, perhaps the smell of tallow, whereas it should be as natural as turning on a light switch.

Joe has detail and it is the observation of someone unusually at home with his subject. Early on we get the first Thousand Bomber Raid (on Cologne) and it was on that night that Grover Williams parachuted into France. Some writers would make a fuss about all the logistics. We'd have Merlin engines bursting into life all over East Anglia whereas Joe points out that it was a Saturday night, when people went dancing, but members of Bomber Command were absent from pubs and dance halls.

Something big was going on, but it was noticeable only in small, local, ways until the next day's newspapers. It is that degree of observation which makes this book so compelling.

|

Motor racing is the hook on which Saward hangs his story, and he is brilliant on prewar motor sport, but it is actually about SOE operations in France. Grover Williams established one network, but there were many others and because Joe has done his research so well, he is able to convey the growth of the Resistance in an organic way, he provides a wide context in which to place his story.

One thing which does emerge is that Benôist became accepted as one of the most important figures in the Resistance due to his natural qualities as a leader. In France, he was a national hero in any case (Williams has never had his proper due in Britain) and since he held a senior position with Bugatti, he was well connected. That helped, but it does not explain how, before he was finally apprehended by the Germans, he was twice arrested and twice escaped.

SOE agents in France usually had a strong connection to the country, but then so had many Germans. The region of Alsace had passed back between France and Germany, there were many Germans who could pass as French and a refreshing part of Joe's narrative is that he gives German counter intelligence its due. They weren't like they have been portrayed in the movies. Saward shows that the German field operatives were a great deal more subtle than the popular image, it was not all black coats, bare light bulbs and pliers on the finger nails. Many were worthy opponents.

Joe has visited everywhere he mentions in The Grand Prix Saboteurs, so his narrative has a sense of place. Nothing is over stated, he gives just enough detail for readers to imagine their own pictures. Joe knows Paris so you move around Paris and the French countryside with he acting as a guide.

The motor racing connection continued throughout the war. Benôist was employed by Bugatti and Ettore Bugatti suspected what was going on. Ettore was still an Italian citizen and Italy was Germany's ally, but he arranged for Benôist to be able to travel throughout France to service Bugattis.

Strictly speaking, this is not a motor racing book. It involves racing drivers, but motor racing itself occupies a very small part of the text. On the other hand, I think it is a profound insight into the mind set of the people who are successful in the sport. Williams, Benôist and Wimille were all outstanding drivers who had competed at a time when the death toll had been high. They volunteered for work where the chances of survival were slim.

Strictly speaking, this is not a motor racing book. It involves racing drivers, but motor racing itself occupies a very small part of the text. On the other hand, I think it is a profound insight into the mind set of the people who are successful in the sport. Williams, Benôist and Wimille were all outstanding drivers who had competed at a time when the death toll had been high. They volunteered for work where the chances of survival were slim.

I once spoke to the late George Abecassis, who holds the record for the driver who has the longest period without defeat. He won the last race at Brooklands 1939 and the first at the 1947 Gransden Lodge meeting, but he had a twinkle in his eye when he said so. George, a co founder of HWM, was noted for his fearlessness at the wheel, it was close to recklessness. Abecassis was one of the pilots who flew SOE agents into Europe. It was dangerous work since there was no fighter cover. George, who died in his bed, said that racing gave him the buzz closest to the buzz he had when flying a lone Halifax over Europe at night.

There are heroics in the book, of course, and also betrayal. Williams was betrayed by a friend, Benôist by an SOE agent under interrogation, and both are shocking stories. On the other hand, few of us know how we would behave if arrested under similar circumstances.

One thing I did learn is that I live about two miles from Tangmere Cottage (now the home of a local physician) where Robert first stayed when he was flown to England to be de briefed. I have long known that Tangmere Cottage was used by the SOE, but that was abstract knowledge, now it is personal. I am sure that I will not be the only reader able to make a connection through a detail like that.

Benôist died by slow strangulation on piano wire in September, 1944, a few weeks after his final arrest. Williams was shot a few weeks before the end of the German surrender having been in a concentration camp for more than 18 months.

A couple of weeks after V J Day, a race meeting was run in the Bois de Boulogne in Paris and Jean Pierre Wimille won the feature race, which was dedicated to the memory of Robert Benôist.

The Grand Prix Saboteurs, by Joe Saward, is soft bound and published by Morienval Press in Paris. At £12.99, US$24.99, it is unusually inexpensive for a book of 363 pages which has both a detailed index and bibliography.

Joe edits Grandprix.com, which we at Pitpass regard as a rival, a rival we hold in great respect it must be said, but a rival nonetheless. The blurbs on the back cover are all written by contributors to Grandprix.com, so they would like it. I have no such reason to recommend this book, but I do and do so without reservation.

It could have been published 16 years ago and nobody except Joe would have known that it was not definitive. He had done his research so well, however, that he knew that he needed to wait until certain documents were released to confirm what he suspected.

His day to day work is always well researched, and he writes well. This, however, it is PhD standard, written better than most novels. I bet that it has taken him to different internal level.

The Grand Prix Saboteurs is a magnificent piece of research and a cracking good read. Saward knows his subject inside out and the really great thing is that he shares his knowledge with the reader and makes the reader his companion.

Mike Lawrence

mike@pitpass.com

To check out previous features from Mike, click here